“It’s given everything to me”: Oropesa’s long baseball journey continues with Osprey

By ANDREW HOUGHTON

For ESPN MISSOULA

The Philadelphia Phillies opened the 2001 season on April 2 in Miami against the Marlins.

For most of the roster, it was a welcome chance to start the season away from the icy spring in Southeastern Pennsylvania, where temperatures were hovering in the 40s.

For 29-year-old rookie reliever Eddie Oropesa, it was the biggest stroke of luck on his winding, nearly decade-long journey to the majors.

“That year we opened the season in Miami against the Marlins, so my family, all my family went to the game,” Oropesa said. “That’s the only way, because I didn’t have money, so if we started the season in Philadelphia, I didn’t have any money to fly my family. So, thank you God that we opened the season in Miami.”

He entered with one out and a runner on third in the seventh, threw two pitches to Cliff Floyd and induced a pop-up on the infield, keeping the runner from scoring and recording his first MLB hold.

Oropesa was removed from the game after pitching to just one batter, but that didn’t diminish the significance of the moment.

Eight years after he left his entire family behind by defecting from Cuba to chase his baseball version of the American dream, they were all there to see him finally reach a major-league mound — his parents, his wife, his son, who hadn’t even met his father until he was three years old.

“It’s difficult when you come from a Latin country to America for the first time, everything is different. But you have to have your mind open and be open to change, because you’re going to change your life forever,” Oropesa said. “Thank you to this country and to the profession of baseball, it’s given everything to me and my family.”

Now a coach for the Missoula Osprey, Oropesa, 46, is barrel-chested and bearded, with an intense stare that recalls Danny Trejo. He speaks heavily-accented English.

His baseball resume reads like a novel, an almost Forrest-Gumpian journey that’s brought him into contact with notable events and players several times.

He was one of the first players to defect from Cuba, beating more famous names like Livan Hernandez, Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez and Danys Baez by several years.

He pitched for the Arizona Diamondbacks in 2002, the year after they won the World Series, and earned the win in the first-ever Major League game ever played at Petco Park in San Diego.

After pitching in the majors for parts of four years following his emotional debut with the Phillies, he hung around the minors and independent leagues until his mid-30s, even pitching in the Netherlands for a while.

“I wanted to keep playing baseball, and the truth is, the only thing I know is to play baseball. It’s difficult, you know,” Oropesa said.

In his post-playing career, he has become something of a mentor for a new generation of Cuban players, hired by the Dodgers to work with star outfielder Yasiel Puig and the Diamondbacks to work with pitcher Yoan Lopez.

In his post-playing career, he has become something of a mentor for a new generation of Cuban players, hired by the Dodgers to work with star outfielder Yasiel Puig and the Diamondbacks to work with pitcher Yoan Lopez.

Oropesa’s experience, the advice that he tried to pass to Puig and Lopez and now to the young Latin players on the Osprey, was hard won.

Very few Cuban players defected to the United States prior to the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Even after, as the economy of the island collapsed and taking slim chances at a major-league salary started gaining appeal, not many players were willing to run the risk.

“Twenty-five years ago, it was tough [to defect], almost nobody did it,” Oropesa said. “They watch you, they have Cuban police with you, so it’s difficult. … You can’t say [your plans] to nobody. I didn’t say even to my family.”

Oropesa grew up in a small town near Matanzas, watching people work in the sugar fields and dreaming about a better life. He saw how his parents struggled, and didn’t want that future for his own family.

Even with the risks associated with defecting — a failed attempt could have meant the end of his baseball career, or repercussions for his family — he decided it was worth the risk.

“First, I wanted freedom, because back in Cuba, it was a communist country,” Oropesa said. “So, I wanted to have a better future for my family, for my son, because back there my wife was pregnant. I know, I grew up in Cuba, it’s difficult to grow up in a country like that.”

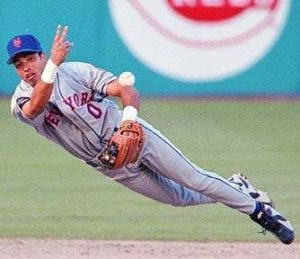

Both Oropesa and shortstop Rey Ordoñez, who would go on to star for the Mets, would defect during the 1993 World University Games in Buffalo, New York.

The plan wasn’t complicated. Oropesa just jumped the outfield fence while warming up before one of the games. He knew what he was giving up — his family, his home, his entire life up until that point — but he just kept running.

“When I made the team, I have the decision already [to defect],” Oropesa said. “So I think, when you have a decision in your life, no one is going to stop you. I jumped the fence in Cuba uniforms, running away from the Cuban team. But I told you, I have my decision already, so I think nobody going to stop me.”

The first three years after Oropesa’s defection were the hardest.

He pitched one year for the independent league St. Paul Saints before signing on with the Dodgers.

One year, he was in Vero Beach, Florida; the next, San Bernardino, California.

His wife, Rita Maria, had been pregnant when he left the country, and not knowing anything about her or the child was hard on him.

Almost all of the money he earned went towards trying to get his family out of Cuba.

“It took me some years [to adjust], especially because the first three years I didn’t want to talk to anybody,” Oropesa said. “The only thing I wanted was to see my wife again and meet my son and see my father, see my mother. So it was difficult.”

Eventually, he did save up enough to bring his family to the States, but life was still hard. A soft-throwing lefty, he didn’t have much margin for error, or the traditional pitchers’ profile that most teams look for.

Oropesa was picked up by the Giants in 1997 and bounced around their system for a while until the Phillies signed him to a minor-league free agent contract before the 2001 season.

That contract, though, came with an invitation to big-league spring training. He was supposed to quickly be sent down to Triple-A, but Oropesa went on one of the great runs of his life, making 13 straight appearances without allowing an earned run and catching the attention of manager Larry Bowa.

As spring training went on and rosters shrunk, he remained in big-league camp and, finally, the word came down — he would heading north with the Phillies when the season started.

“It was difficult, especially the last week, because everybody asks, ‘Hey, you making the team, you make the team?’” Oropesa said. “So, probably I didn’t sleep for two, three days. Finally they call me to the office, they give me the news. I started crying, yeah.”

That game in Miami was the high point of Oropesa’s career, but he would go on to pitch in 125 games in the major leagues. After that came a few more years in the minors, his detour to the Netherlands, and then a coaching career.

He started working with high school kids in Miami before his former team, the Dodgers, gave him a call when they signed the talented but mercurial Puig in 2012. When the outfielder lit the baseball world on fire as a star rookie in 2013, Oropesa was right there with him.

Almost as soon as Puig established himself in the majors, Oropesa found himself working with Lopez, another big-money Cuban signing, this time for the Diamondbacks. After all that, he found himself in Missoula to start 2018, working with his former minor-league teammate, Osprey manager Mike Benjamin.

Coaches like Oropesa are a valuable resource for the young Latin American players that come through Missoula every year, and he’s happy to share his experiences and advice. Missoula is a long way from Cuba, or from Miami, where Oropesa made his debut so long ago.

But working in Montana, passing down his hard-won knowledge, is an appropriate fit for a man who’s been everywhere and seen everything.

“The advice, especially with Latin guys, is, ‘Make your mind open to change, because the baseball in America is different than anywhere.’ Different country, playing professional baseball, that’s the difficult part for the Latin guys,” Oropesa said. “I want to thank the Diamondbacks for giving me the opportunity, because I want to be in the position that I’m in now, like, try to help [the players], especially the Latins. I’m so happy with what I do right now.”

Oh, and the unborn son he left behind in Cuba?

Eddie Oropesa Jr. became a pitcher too. He didn’t have the same talent as his father, but pitched for a number of years in college, and even briefly for the same Dutch team, the Mampaey Hawks, as his old man.

Even with all the memories he’s racked up in his years playing baseball, there’s nothing that makes Eddie Oropesa Sr. happier than to have given his son the opportunity to follow in his footsteps.

“It’s good, because I was doing everything for him,” Oropesa said. “Because I remember when I grow up, I see my mother and my father start struggling back in Cuba to give me food, to give me everything, my two sisters and me. I didn’t want my son going through that shit. That’s why I make the decision to come to America. … For me, that’s the whole point of my life.”

Andrew Houghton is a freelance journalist providing weekly feature stories about the Missoula Osprey for ESPN Missoula. His work can also be found at skylinesportsmt.com.

Got something to say?